Clothing & attire

In chapter (7-75,) Herodotus mentions that Thracians used to wear fox skin during winter and to this day we find that Thracians are recognized by this cap in ancient illustrations. They used to wear a tunic with a colorful cloak on top (zeiras) and wear sandals made of deer skin on their feet. It was difficult to distinguish between their hemp and linen clothes in the summer. Combined elements of ancient Greek and Byzantine origin compose the sartorial patterns of Thrace and were introduced to us in late 19 th century. Ever since the beginning of Ottoman Empire, the sartorial map of Thrace has been composed of various ethnic and cultural origin groups, who lived there such as Armenians, Jews, Ottomans, Greeks, Pomaks and Roma.

The economic affluence and the new social conditions in urban centers, contributed to the rapid urbanization of garments. European attire donned by upper class had a big impact on the way regional country folk would dress. The rural population that lived in a closed stock-farming economy, used to always construct the same type of clothes. Each group’s aesthetics were expressed through shapes, colors and accessories that constituted an information code regarding their economic and professional activities, their age and their role in society as well as the current

aesthetics.

During the Lozanne treaty in 1923, with the refugee settlement from Asia Minor to N.E. Thrace, the sartorial map of Thrace changed dramatically.

With the drastic social changes in the area in 1960 such as immigration, and television, people’s relationship with clothes altered and traditional attire was abandoned.

Worship & devotional cycle

Time, the cycle of life, the land, the vegetation, the rain, the crop, the seed, the perpetual cycle of creation, the human kind and The Divine, all make up for a primordial skein that emerges through customary activities, symbols and meanings of a different era, a different way of life, with the power to reveal the signs of an inward and social evolution.

Music in Thrace consists of traditional sounds that accompany Thracians to all their big life moments such as their birth and wedding, times of loss, suspense and longing, with weather rituals for the fertility of the land while at the forefront of the endless seed sowing cycle, and of death and nature revival.

The invocation and gratitude to Mother Earth, the Saints and God, are imprinted on the Holy Vessels in areas of worship, on traditional objects of worship cycle of the wider Thrace region, in customs and rituals whose performance is interwoven with people’s suspense and expectations for the year, hoping to somehow trap the good and to keep evil at bay.

All these activities that have the power to reveal the signs of a personal and therefore inward and social evolution, instigate the following:

The rousing of a priceless treasure of images that everyone bears inside and has forgotten about, the re- discovering of symbolical thought and meaning, the atomic and collective purification and the wealth found in such behaviors.

The re-discovering of family and local tradition, as well as the time and the place where people first began their journey as individuals and social beings.

Nutrition

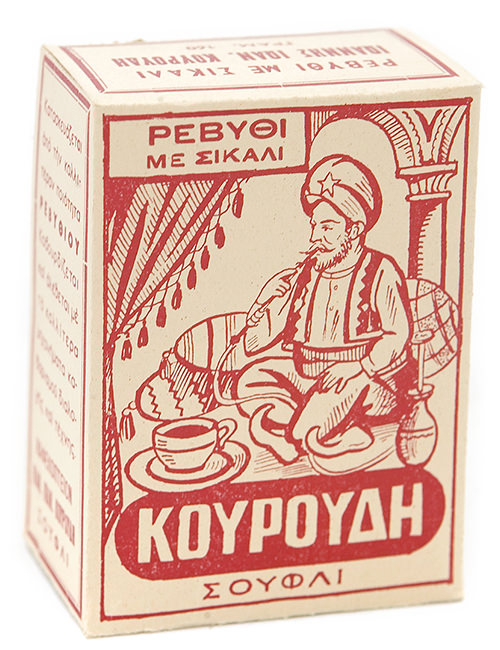

Nutrition has been a custom of worship since the ancient times, either through sacrifice and libation to the gods, or through offerings to the Christian Saints. The life experiences of the ancient world, as well as the gastronomic habits of the Byzantine, were enriched with the cultural experiences of nomads and urban folk of different ethnicities that settled in Thrace and the rest of Greece during the Ottoman times. The gastronomic habits of the Greeks in Asia Minor, Black Sea, Kappadokia and North Eastern Thrace, have enriched and transformed Greek cuisine. The mixture of products, aromas, seasoning and the lusciousness of various flavors the Ottomans had brought from the Orient would later transform Constantinople cuisine. Through the rich and various nutritional customs of urban and country folk of different ethnicities of Thrace, the traces of cultural rearrangement and influence these people received, are saved to this day. In traditional urban folk world, the kitchen is the center of social and collective life. They used to divide their days into fasting or non- fasting days depending on Saint celebration days. The skillful concoctions of urban cuisine, were created through seeking sophisticated, hedonistic tastes and the creative imagination of scholars.

The various forgotten authentic tastes of Thrace reel people in and lead them to the luxury and magic of tradition.

Copperware & Pottery

Copperware

Increasing use of copperware for domestic purposes has led to the development of the coppersmith’s craft, which flourished during the 18 th and 19 th century. Dowry arrangements of this period, reveal copperware’s significance in domestic economy. The most important center for copperware manufacture was Constantinople (Istanbul), where Greek craftsmen, mainly from the Black Sea, were considered the best.The majority of coppersmith workshops were In Western Thrace, Xanthi and Komotini, whereas in Alexandroupolis, there was a repair shop. Beaten copper technique, went on until 1955-1960, while up until 1975 only rural folk would buy copper, as it was associated with their traditional way of life. Beaten copperware was simple and functional and with or without decoration. People recognized it at holiday gatherings and donations from the engraved dedicational or proprietorial inscriptions.

Pottery

The pottery workshops in Xanthi, Komotini, Alexandroupolis, Ferres, Soufli, Didymoticho, Metaxades produced simple, utilitarian pottery such as chimney pots, water pipes, cooking pots, milking pails, jugs, flower pots and vases. The Greek pottery makers who arrived after 1922 from well- known pottery- making centers of The Black Sea, Asia Minor, Eastern and North Eastern Thrace, kept the pottery-making tradition going at their new destination. Their output was adapted to the shapes of the local, established pottery-makers and the needs of simple households. Canakkale workshops were the main suppliers of pottery to the rich of the region. Canakkale was established as the center for pottery-making between 1670 and 1922. Kostas Voivontoudis in Metaxades and Papavlasakoudis in Soufli, are the last pottery-makers in S. Evros.

Cultivation of the land

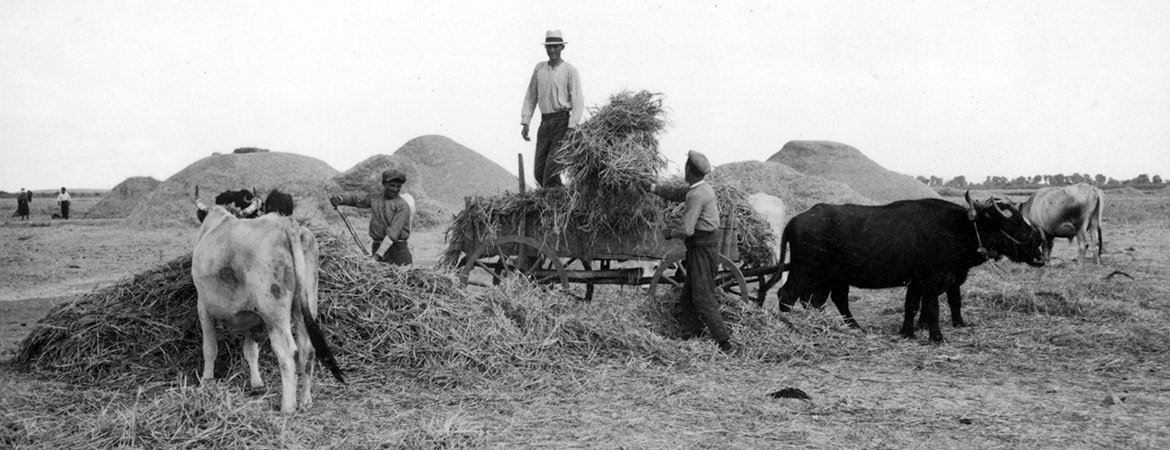

From prehistoric times, to the age of mechanical cultivation, the agricultural economy has very slowly gone through various stages. Under Ottoman rule, the manner of utilising the land was the same across the whole Ottoman Empire. There were large estates (çiflikia), where slaves, provided by the landholder, would work in barely basic conditions, under the supervision of an overseer (dragoumani). Other estates used the system of sharecropping (tenant farmers used to rent the land and give the landowner a portion of the profits.)

When Thrace was integrated into the free Greek State, Ottomans’ çiflikia were bought by rich Greeks. Greek farmers used to cultivate legume, maize, sugarcane, sesame, flax, sorgo, tobacco but mostly cereal in smaller pieces of land, to cover their eating habits. Despite the fact that for centuries cultivation of wheat and barley were the main cultivated products, the produce could not cover farmers’ needs, so they would ensure they had the required quantity through the exchange of other products.

The distribution of the land to non-owners began in 1933. Land consolidation, flood control, drainage, irrigation work started much later and rendered new, more fertile pieces of land for cultivation, with products like beetroot, cotton and maize.

Cultivation of Cereals

The first rains in October signal the start of sowing. The fields are dug over 2 or 3 times with a wooden plough (aletri) or an iron plough (papara). Reaping was done in July with sickles, and the reapers wore a kind of wooden glove (palamaria) on their left hand or long wooden thimbles (daktylithres) to protect their hand and to enable them to carry a larger number of cornstalks. The cut stalks were tied together to make sheaves (dematia), which were gathered together in stacks. The threshing was done with the adokana or doukana, a timber beam dragged around the threshing floor by animals. The constant movement of the beam would break up the corn. The workers used a wooden implement known as a sklavoura to collect the coarse straw and take it to the barn for storage. The rest ― grain and chaff ― was piled up and tossed into the air with a wooden pitchfork (lihnitiri). The wind carried off the chaff, and the grain fell to the ground. The grain was then sifted with a riddle (starodermono), transferred to sacks, and carried home. The unit of measurement for corn was the sniki (or the pnak on Samothraki).

Four snikia were equivalent to a kilo of grain, or enough to sow a field of 2,000 m2 (two stremmas or approximately half an acre). People would talk about a ‘one-kilo field’, rather than a ‘two-stremma field’, which was the official unit of measurement. On Samothraki, because most of the islanders raised livestock, the expression ‘a one-head fold’ was used as a unit for measuring a variable land area. The better the soil, the smaller the ‘fold’.

Tobacco

In Thrace a variety of ‘oriental tobacco’ known as basma was cultivated. The steady rise in tobacco use and the expansion of the tobacco market led to the creation of a separate professional group in the period of Ottoman rule, the guild of tobacco-merchants (toutoundzides). Xanthi, which produced the ‘king of tobaccos’, became the home of the 3 largest tobacco companies in Greece. The state of the world tobacco market, coupled with events in local history (wars, enemy occupation, and an influx of refugees), meant that the tobacco economy went through periods of growth, decline, and stability; but it was also the cause of a profound social crisis, when a dispute between tobacco merchants and tobacco workers developed into a class struggle.

Sowing in the nurseries begins on 15 March, and in late May or early June the tobacco growers start planting out. Two months later, harvesting begins, starting with the bottom leaves, which mature first. The leaves are taken home in baskets, and then strung in bunches using large needles. The bunches are hung up on drying frames (xirandiria) for 8-15 days to dry out. Then the leaves are placed neatly one on top of the other and arranged in very orderly fashion in the kapakia to be flattened. Lastly, the tobacco leaves are packed in a wooden structure known as the sendouki, where they are maintained in good condition until the time comes for them to be assessed, sold, and transported to the warehouses.

Wine

In ‘vine-rich’ Thrace, thickly dotted with vineyards, the deified ancestor Dionysos or Bacchos taught the art of viticulture. They say that the area of the southern Black Sea was thick with vineyards from earliest antiquity, and that viticulture spread via Palestine to Libya and thence to Crete. Also thickly dotted with vineyards were the hills around Soufli, where grapes were believed to predate sericulture. Because they did not have appropriate means of processing it, and also owing to the sheer volume produced, the Thracians were unable to dispose of the blessed fruit otherwise than by using wine instead of water in the mortar with which they built their houses. It is worth noting that wine production in the Ottoman province of Edirne in the nineteenth century was 42 million litres, of which 75 per cent was exported to France; and 5 per cent of it (2 million litres or so) came from Soufli. Grapes were also offered in church, together with corn, as first-fruits. Indeed, by decision of the Third Oecumenical Council, it was ordained (on pain of unfrocking) that the priest should bless the offering of grapes separately and that they should then be distributed among the faithful ‘in thanks to the giver of the fruits’. The custom continues in Thrace and elsewhere on 6 August, the feast of the Transfiguration. The place of the deified Bacchos/Dionysos as teacher and patron of viticulture was taken in the Christian era by St Tryphon, patron of the vine.

Temporary Exhibits

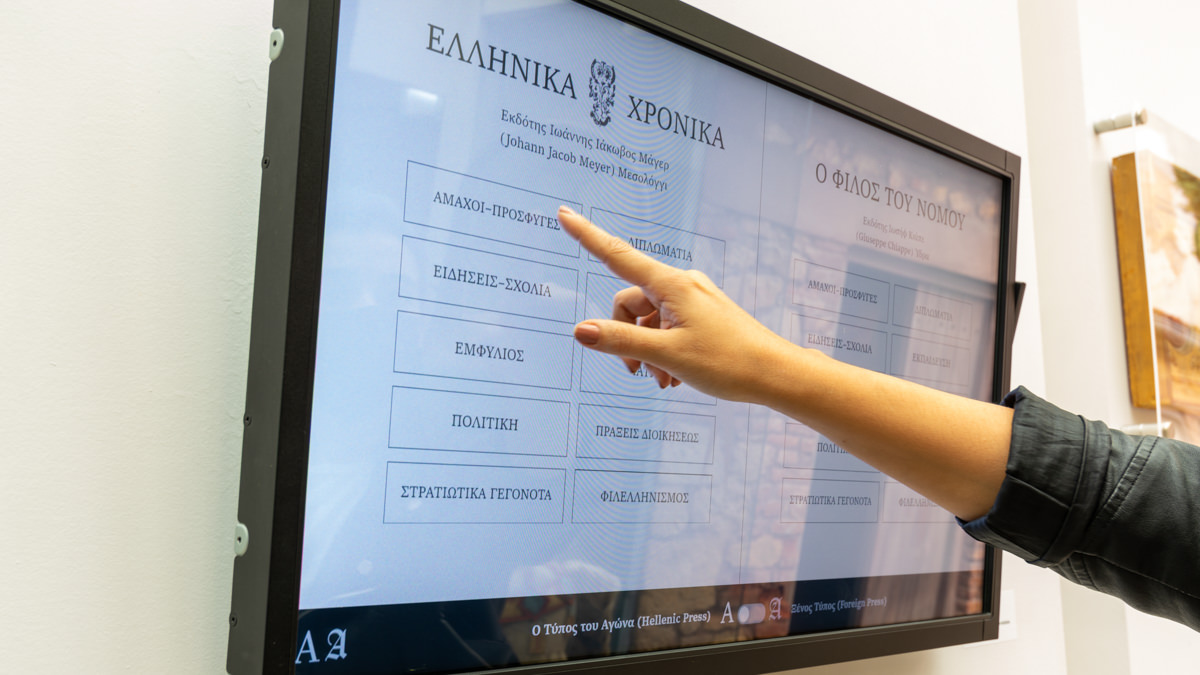

Temporary exhibitions, set up for a period of one to six months, introduce fresh material to the visitor.

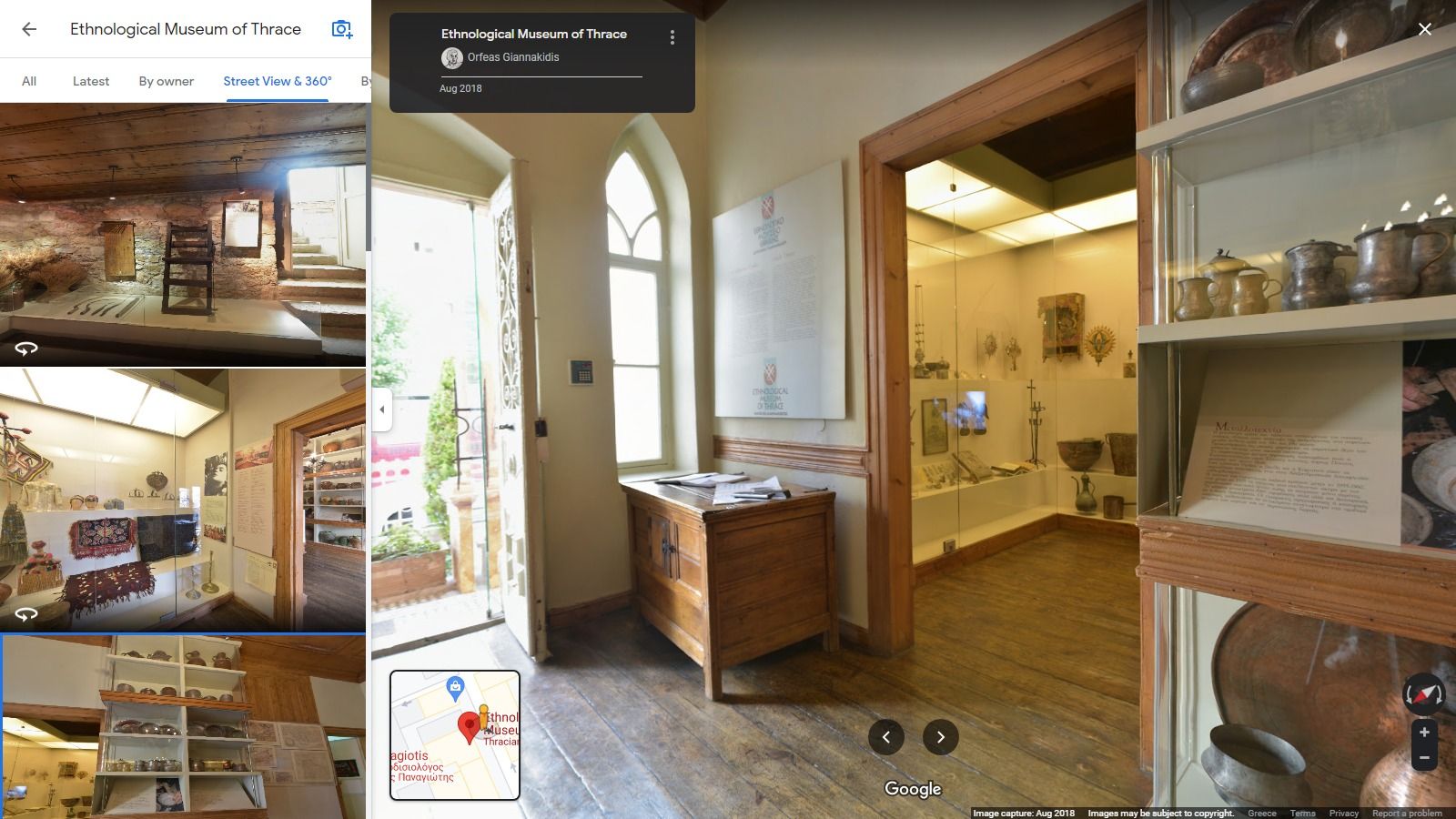

Virtual Tour

Take a virtual tour of the museum through high resolution 360o panoramic photos